In Chunhui Children’s “Mom’s Time Museum” exhibition, a medal with worn, polished edges lies quietly in a glass display case. Alongside it was a faded milk powder can- turned stool, a pilling scarf, and other aged belongings—fragments that together portray the everyday moments of care for orphaned children in a welfare institution.

That medal preserves the memory of 238 days of cheerleading training by a visually impaired girl named Xinxin—and also encapsulates the 25 years of loving care Chunhui Mamas provided for over 210,000 children.

The medal emits a gentle luster under the light, its edges smoothed by touch like a cocoon spun from time. Chunhui Mama Yang Zhongfang often finds herself staring at it in a daze, vividly recalling the day Xinxin first arrived:

a messy ponytail, school uniform sleeves two fingers short, pale knuckles clutching a canvas bag—like a little daisy bent in the wind.

Xinxin’s Medal

Xinxin had just turned seven. Retinitis pigmentosa had reduced her world to blurry light and shadow. At night, Mama Yang would often hear rustling from the top bunk where Xinxin sleeps. Opening the curtain, she’d find the child curled into a tiny ball, the quilt trembling gently.

The next morning, when Xinxin combed her tangled hair, the plastic comb would snag at the ends. Xinxin would sit still and suddenly whisper, “Mama, can I have a bow?” That was when Mama Yang found a faded sticker hidden under her pillow—a cartoon girl with a pink bow in her hair.

On the day Xinxin was sent to Nanshan Special Education Center, a light rain fell over the train platform. Her palm, gripping the white cane, was drenched in sweat. Suddenly, she turned and hugged Mama Yang’s waist:

“Mom… I’m scared.”

Her voice was muffled in Mama Yang’s clothes, but it reminded Yang of the first time she washed Xinxin’s hair—how the water trickled down her lashes, and she bit her lip silently, refusing to cry.

“Don’t be afraid, Mama will pick you up every Saturday,” she whispered, stroking the soft fuzz at the back of Xinxin’s neck. “I left your favorite strawberry lip balm by your dorm bed. If you miss Mama, just put a little on.”

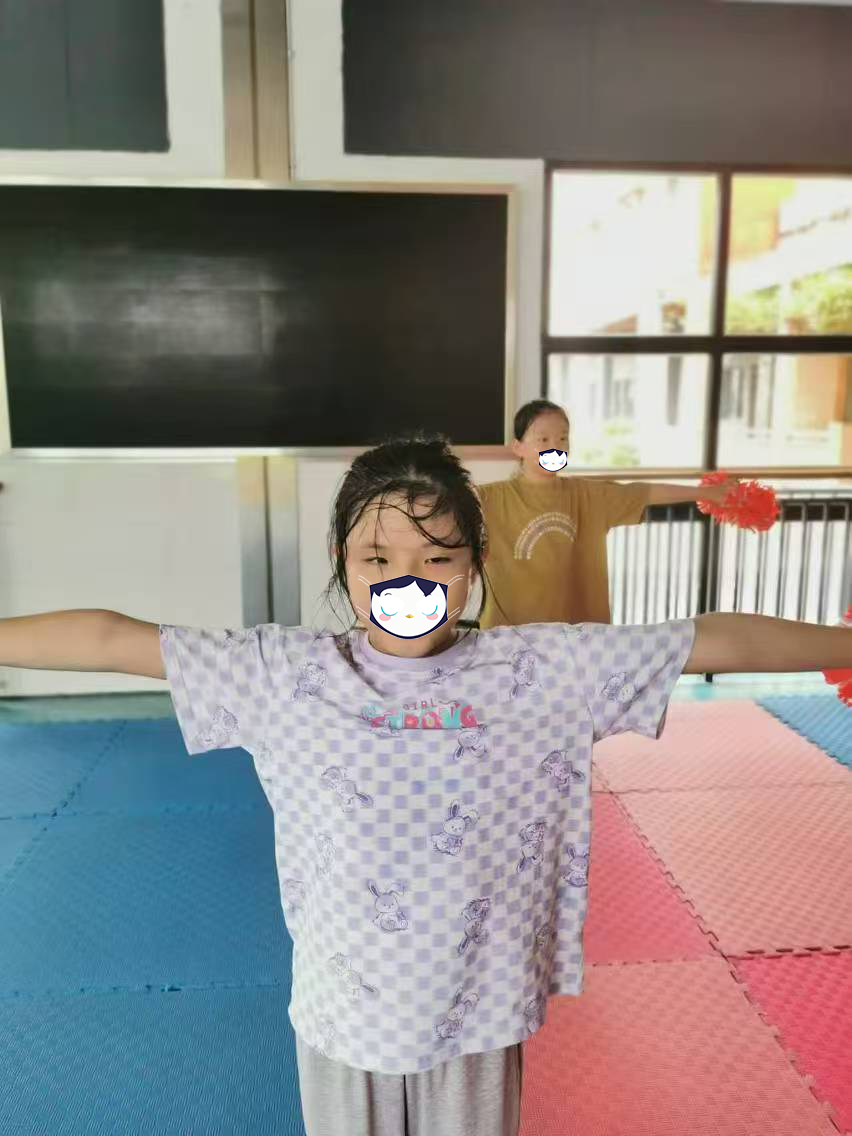

Xinxin in Rehearsal

Three months later, during a phone call, the homeroom teacher said Xinxin was frozen in place, staring at the cheerleading squad on the playground. Via video, Mama Yang saw her daughter gently feeling her teammates’ wrists to sense the curve of each movement, tracing invisible shapes in the air with her fingertips.

“But I can’t see the moves…” Xinxin’s voice wavered with doubt, but Mama Yang recognized the determined set of her mouth—the same look she had the first time she washed her socks on her own.

“Just follow the rhythm of the music,” Mama Yang said, gesturing at the screen. “Remember how I taught you to count the stairs?” She smiled, “And the voice-activated lights in our hallway? Tap, tap, tap—every beat lights up a step. Each move is just like that light—clear and bright.”

That summer, the city was a giant steamer. In the training hall of the special school, old fans creaked and groaned. Xinxin wore a faded uniform, her knees red from the friction of knee pads. Every weekend, Mama Yang came to deliver clean clothes and always saw her practicing with a tape recorder. Whenever she sensed a beat was off, Xinxin would tap her white cane and ask, “Auntie, does the chorus start on the third beat?” Sweat dripped from her chin onto the floor, but she insisted on rewinding the tape until the movements matched the drumbeats exactly.

One stormy night during a blackout, she practiced against the wall twenty times. The next day, she touched the tape recorder and said, “Mama, I’ve memorized the position of every button.”

The night before the competition, Mama Yang ironed her team uniform under the dorm lamp. The gold-threaded crest shimmered. Xinxin suddenly touched the iron mark on Yang’s hand. “Does it hurt?” she asked, tracing it with the same care she used to read her braille textbooks.

“No, it doesn’t,” Mama Yang replied, looking at the number tag on Xinxin’s chest. She suddenly recalled the first time she taught her to tie shoelaces. Those small hands fumbled in the dark for half an hour but finally managed to tie a neat butterfly knot on the tenth try.

At the award ceremony, sunlight flooded the stadium. Xinxin stood on the podium, the medal on her chest catching the light in fine glimmers. She turned toward the audience—though she couldn’t see, the curve of her smile held an entire spring.

After stepping down, she immediately reached for Mama Yang’s hand and placed the medal in her palm. “Mama, touch it.”

The uneven surface of the metal pressed into her hand—hard and cold, yet filled with warmth.

Today, the medal still rests in the most prominent spot in their living room, beside a scarf Xinxin had just knitted. Its crooked stitches hold a yarn ball tucked inside.

Mama Yang often thinks back to that summer of relentless practice in the dark—to the way her daughter counted the beats of music.

She now understands: the most moving form of growth is not a miraculous surge, but the quiet perseverance of a blind child learning to touch the world—turning every effort into a glowing mark, one fingertip at a time.